Increased breadth of testing

Even within one specific tumour type, the key genes driving tumour growth and spread can vary significantly from one patient to the next. Looking at each of the likely genes individually is slower, can be considerably more expensive and will need more sample (which can be a problem with today’s minimally invasive, but also tiny biopsies). Next generation sequencing allows us to look at all the most relevant genes from multiple patients simultaneously.

Increased depth of testing

Mutations within a tumour may only make up a proportion of the DNA derived from it. Furthermore, samples sent for testing will always contain a component of normal cells (unrelated to the tumour), which can sometimes significantly out number the tumour cells. All this ‘normal’ DNA, effectively dilutes that from the tumour, potentially making identifying tumour specific mutations akin to looking for a needle in a haystack. Next generation sequencing effectively allows us to analyse single molecules of DNA from within the sample, the more of these that we analyse, known as the sampling or ‘read’ depth, the less likely we are to miss any. The adjustment of test sensitivity by changing the sampling depth is not something that is so readily achievable with other technologies.

Increased range of identifiable variations

In one form or another, NGS techniques can be use to identify all the different types of genetic variations relevant in cancer (single nucleotide variants, small insertions/deletions/substitutions, large scale rearrangements and copy number variations). Also, unlike many other techniques, it isn’t restricted to only being able to identify variants that are already known, with ‘novel’ variants often being identified which would still be considered actionable.

How cancers begin: mutations within genes

Each one of our cells contains thousands of genes.

As we get older, we develop mutations* within our genes – some are caused by outside factors like smoking or sun damage, while others happen at random.

If a normal cell accumulates enough mutations in enough key genes, it can become a cancer cell. It can then multiply quickly to create a tumour.

Through genetic testing, we can take a sample of a tumour, look at its DNA, and understand which genes have mutated – and therefore which treatments might be best for the individual patient.

*These are know as ‘acquired’ or somatic mutations, and are not inherited from our parents. Inherited (or germline) mutations do occur that predispose to certain cancer types such as breast or ovarian, but different types of tests are more appropriate for investigating these.

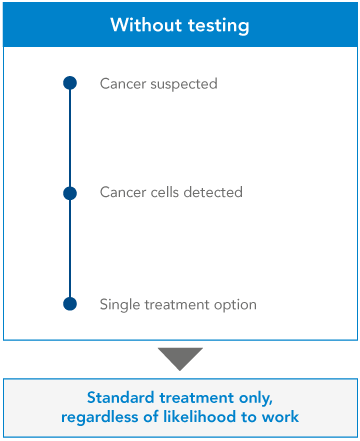

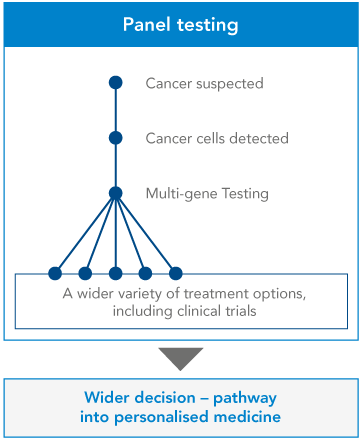

From single gene testing…

At the moment, many clinicians use ‘single gene testing’ to learn more about a patient’s cancer. The clinician will have already requested some initial investigations, to determine the origin and the type of cancer. They’ll know which approved drugs may work, and they’ll know which gene they can test to confirm this – so they’ll test that single gene. If the gene shows certain mutations, the clinician will recommend a certain treatment. If not, they’ll give the patient a different treatment.

It’s a yes-or-no, black-and-white approach. But it’s inefficient. Clinicians can get more information, and more options for their patient, by examining a number of genes at once.

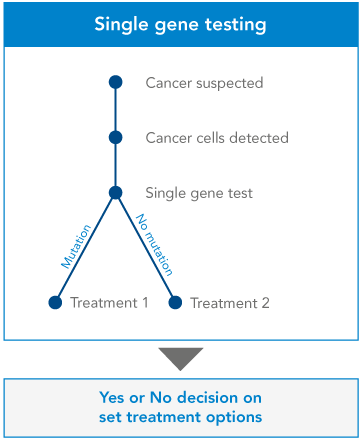

…to Next Generation Sequencing

Next Generation Sequencing allows clinicians to examine multiple genes within a tumour – known as a ‘panel’ of genes – all at once. As well as indicating which treatments are likely to work, and which are unlikely to work, these multiple-gene tests can clarify certain ambiguities in the diagnosis, and may shed some light on the patient’s prognosis. Test results can also show whether the patient might be right for a clinical trial, giving them more options about what to do next.

Some of this extra information can be critical for a patient. For instance, a single gene test might indicate that a tumour is showing a certain mutation in a certain gene. But a multiple-gene test could show that this mutation is taking place alongside another mutation or mutations – which might lead clinicians to suggest a different treatment path for the patient.